Welcome to Mongolia

Duration:

DATES:

TOUR HIGHLIGHTS:

Mongolia, the country of adventure, land of blue sky and vast steppe with real nomads, freedom and great history behind. Mongolians are welcome hospitality nation to introduce our nomadic lifestyle to you and proud to share their amazing history with you.

INTRODUCTION AND QUICK FACTS

Mongolia, landlocked country located in north-central Asia. It is roughly oval in shape, measuring 1,486 miles (2,392 km) from west to east and, at its maximum, 782 miles (1,259 km) from north to south.

Mongolia’s land area is roughly equivalent to that of the countries of western and central Europe, and it lies in a similar latitude range. The national capital, Ulaanbaatar (Mongolian: Ulan Bator), is in the north-central part of the country.

Landlocked Mongolia is located between Russia to the north and China to the south, deep within the interior of eastern Asia far from any ocean. The country has a marked continental climate, with long cold winters and short cool-to-hot summers. Its remarkable variety of scenery consists largely of upland steppes, semideserts, and deserts, although in the west and north forested high mountain ranges alternate with lake-dotted basins. Mongolia is largely a plateau, with an average elevation of about 5,180 feet (1,580 metres) above sea level. The highest peaks are in the Mongolian Altai Mountains (Mongol Altain Nuruu) in the southwest, a branch of the Altai Mountains system.

Some three-fourths of Mongolia’s area consists of pasturelands, which support the immense herds of grazing livestock for which the country is known. The remaining area is about equally divided between forests and barren deserts, with only a tiny fraction of the land under crops. With a total population of fewer than three million, Mongolia has one of the lowest average population densities of any country in the world.

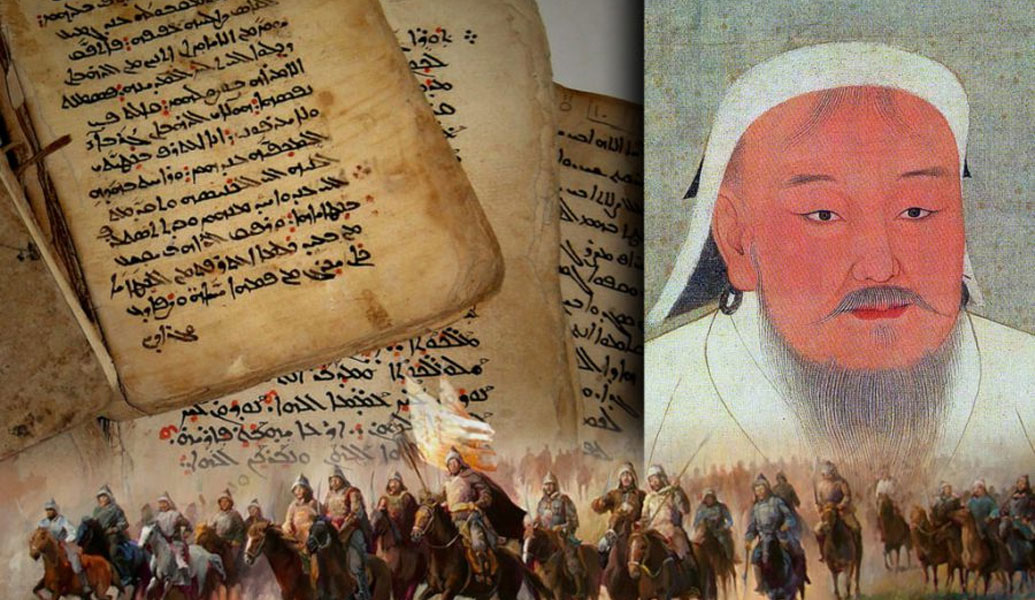

The Mongols have a long prehistory and a most remarkable history. The Huns, a people who lived in Central Asia from the 3rd to the 1st century BCE, may have been their ancestors. A united Mongolian state of nomadic tribes was formed in the early 13th century CE by Genghis Khan, and his successors controlled a vast empire that included much of China, Russia, Central Asia, and the Middle East. The Mongol empire eventually collapsed and split up, and from 1691 northern Mongolia was colonized by Qing (Manchu) China. With the collapse of Qing rule in Mongolia in 1911/12, the Bogd Gegeen (or Javzandamba), Mongolia’s religious leader, was proclaimed Bogd Khan, or head of state. He declared Mongolia’s independence, but only autonomy under China’s suzerainty was achieved. From 1919, nationalist revolutionaries, with Soviet assistance, drove out Chinese troops attempting to reoccupy Mongolia, and in 1921 they expelled the invading White Russian cavalry. July 11, 1921, then became celebrated as the anniversary of the revolution. The Mongolian People’s Republic was proclaimed in November 1924, and the Mongolian capital, centred on the main monastery of the Bogd Gegeen, was renamed Ulaanbaatar (“Red Hero”).

LAND

Mongolia can be divided into three major topographic zones: the mountain chains that dominate the northern and western areas, the basin areas situated between and around them, and the enormous upland plateau belt that lies across the southern and eastern sectors. The entire country is prone to seismic movements, and some earthquakes are extremely severe. Their effects, however, are limited by the low population density.

The mountains

There are three major mountain chains in Mongolia: the Mongolian Altai Mountains, the Khangai Mountains (Khangain [or Hangayn] Nuruu), and the Khentii Mountains (Khentiin [or Hentiyn] Nuruu). The Mongolian Altai in the west and southwest constitute the highest and the longest of these chains. Branching southeastward from the main Altai range at the northwestern border with Russia, the Mongolian Altai stretch southeastward for some 250 miles (400 km) along the Chinese border before turning slightly more eastward for another 450 miles (725 km) in southwestern Mongolia. The range—the only one in the country where contemporary glaciation has developed—reaches an elevation of 14,350 feet (4,374 metres) at Khüiten Peak (Nayramadlyn Orgil) at the western tip of the country, Mongolia’s highest point. Extending eastward from the Mongolian Altai are the Gobi Altai Mountains (Govi Altain Nuruu), a lesser range of denuded hills that lose themselves in the expanses of the Gobi.

The northern intermontane basins

Around and between the main ranges lie an important series of basins. The Great Lakes region, with more than 300 lakes, is tucked between the Mongolian Altai, the Khangai, and the mountains along the border with Siberia. Another basin lies between the eastern slopes of the Khangai Mountains and the western foothills of the Khentii range. The southern part of it—the basins of the Tuul and Orkhon (Orhon) rivers—is a fertile region important in Mongolian history as the cradle of settled ways of life.

The remarkable Khorgo region, on the northern flanks of the Khangai Mountains, has a dozen extinct volcanoes and numerous volcanic lakes. Swift and turbulent rivers have cut jagged gorges. The source stream of the Orkhon River is in another volcanic region, with deep volcanic vents and hot springs. Near the northern border, Lake Khövsgöl (Hövsgöl) is the focus of another rugged region that is noted for its marshlands.

The plateau and desert belt

The eastern part of Mongolia has a rolling topography of hilly steppe plains. Here and there, small, stubby massifs contain the clearly discernible cones of extinct volcanoes. The Dariganga area of far eastern Mongolia contains some 220 such extinct volcanoes. Most of the southern part of the country is a vast plain, with occasional oases, forming the northern fringe of the Eastern (Mongolian) Gobi. The flat relief is occasionally broken by low, heavily eroded ranges. Several spectacular natural features are found in the Gobi region. Huge six-sided basalt columns, arranged in clusters resembling bundles of pencils, are found in the eastern and central regions. The southern Gobi contains a mountain range, the Gurvan Saikhan (“Three Beauties”), that is known for its dinosaur fossil finds at Bayanzag and Nemegt. In addition, the range’s scenic Yolyn Am (Lammergeier Valley)—now a national park, with a deep gorge containing a small perennial glacier—is surrounded by towering rocky cliffs where lammergeiers (bearded vultures) roost.

Climate and soils

Situated at high latitudes (between 41° and 52° N) and high elevations (averaging about 5,180 feet [1,580 metres]), Mongolia is far from the moderating influences of the ocean—at its nearest point some 435 miles (700 km) west of the Bo Hai (Gulf of Chihli). Consequently, it experiences a pronounced continental climate with very cold winters (dominated by anticyclones centred over Siberia), cool to hot summers, large annual and diurnal ranges in temperature, and generally scanty precipitation. The difference between the mean temperatures of January and July can reach 80 °F (44 °C), and temperature variations of as much as 55 °F (30 °C) can occur in a single day. Mean temperatures in the north generally are cooler than those in the south: the mean January and July temperatures for the Ulaanbaatar area are −7 °F (−22 °C) and 63 °F (17 °C), respectively, while the corresponding temperatures for the Gobi area are 5 °F (−15 °C) and 70 °F (21 °C).

Precipitation increases with elevation and latitude, with annual amounts ranging from less than 4 inches (100 mm) in some of the low-lying desert areas of the south and west to about 14 inches (350 mm) in the northern mountains; Ulaanbaatar receives about 10 inches (250 mm) annually. The precipitation, which typically occurs as thunderstorms during the summer months, is highly variable in amount and timing and fluctuates considerably from year to year.

A remarkable feature of Mongolia’s climate is the number of clear, sunny days, averaging between 220 and 260 each year, yet the weather may also be severe and unpredictable. Sandstorms or hailstorms can develop quite suddenly. Heavy snow occurs mainly in the mountain regions, but fierce blizzards sweep across the steppes. Even a thin coating of ice or icy snow can prevent animals from getting to their pasture.

PEOPLE

Ethnic background and languages

Archaeological remains dating to the earliest days of prehistory have attracted the attention of Mongolian and foreign scholars. The Mongols are quite homogeneous, ethnically. Within Mongolia, Khalkh (or Khalkha) Mongols constitute some four-fifths of the population. Other Mongolian groups—including Dörvöd (Dörbed), Buryat, Bayad, and Dariganga—account for nearly half of the rest of the population. Much of the remainder consists of Turkic-speaking peoples—mainly Kazakhs, some Tuvans (Mongolian: Uriankhai), and a few Tsaatans (Dhukha)—who live mostly in the western part of the country. There are small numbers of Russians and Chinese, who are found mainly in the towns. The government has given increased attention to respecting and protecting the languages and cultural rights of Kazakhs, Tuvans, and other minorities.

The vast majority of the population speaks Mongolian, and nearly all those who speak another language understand Mongolian. In the 1940s the traditional Mongolian vertical script was replaced by a Cyrillic script based on the Russian alphabet. (This was the origin of the transliteration Ulaanbaatar for Ulan Bator, the traditional spelling.) In the 1990s the traditional script was once again taught in schools, and store signs appeared in both Cyrillic and traditional forms.

Religions

The Mongols originally followed shamanistic practices, but they broadly adopted Tibetan Buddhism (Lamaism)—with an admixture of shamanistic elements—during the Qing period. On the fall of the Qing in the early 20th century, control of Mongolia lay in the hands of the incarnation (khutagt) of the Tibetan Javzandamba (spiritual leader) and of the higher clergy, together with various local khans, princes, and noblemen. The new regime installed in 1921 sought to replace feudal and religious structures with socialist and secular forms. During the 1930s the ruling revolutionary party, which espoused atheism, destroyed or closed monasteries, confiscated their livestock and landholdings, induced large numbers of monks (lamas) to renounce religious life, and killed those who resisted.

In the mid-1940s the Gandan monastery in Ulaanbaatar was reopened, and the communist government began encouraging small numbers of lamas to attend international Buddhist conferences—especially in Southeast Asia—as political promotion for Mongolia. The end of one-party rule in 1990 allowed for the popular resurgence of Tibetan Buddhism, the rebuilding of ruined monasteries and temples, and the rebirth of the religious vocation. Buddhists, predominently of the Dge-lugs-pa (Gelugspa; Yellow Hat) school headed by the Dalai Lama, constitute nearly one-fourth of Mongolians who actively profess religious beliefs. Approximately one-third of the population adheres to traditional shamanic beliefs. A relatively small number of Muslims, who are found mostly in the western part of the country, are nearly all Kazakhs, and a much smaller community of Christians of various denominations live mainly in the capital. A significant proportion of the people are atheistic or nonreligious.

CULTURE LIFE

Contemporary cultural life in Mongolia is a unique amalgam of traditional nomadic, shamanic, and Buddhist beliefs—now free from the Marxist doctrine overlaid during the socialist period but vulnerable to powerful new foreign influences. Once-despised commercialism has come to drive national prosperity at the risk of harming the national heritage and environment. Images of Genghis Khan, the revered symbol of Mongol nationhood, now are used to advertise vodka and beer. Cultural affairs fall within the purview of the directorate in charge of culture and art within the Ministry of Education, Culture, and Science. The government pursues cultural policies, funding the arts in the name of the national interest. However, the life support provided during the socialist period by the ruling party for compliant writers, artists, and musicians no longer exists, and those groups have formed associations—such as the Arts Council and the Union of Art Workers—to represent their interests.

Daily life and social customs

Urbanization and modernization inevitably have had a heavy impact on nomadic traditions in Mongolia, but many of the distinctive old conventions have continued. The ger (yurt) is always pitched with its door to the south. Inside, the north is the place of honour, where images of the Buddha and family photographs are kept. The west side of the ger is considered the man’s domain, where his saddle and tack are stored, as well as a skin bag of koumiss, or airag in Mongolian (fermented mare’s milk), hanging from a wooden stand. The east side is the woman’s, where food is prepared and utensils stored. The stove stands at the centre, its chimney passing through the roof. It is considered a sign of disrespect to the host if anyone entering the ger should step on the threshold. Male visitors will exchange snuff bottles for a pinch of each other’s snuff. Typically, milky tea (süütei tsai), koumiss, or vodka (arkhi) is served in a bowl of porcelain or wood and silver, presented by the host and received by the guest with the right hand, the right arm supported at the elbow by the left hand.

Another feature of traditional Mongolian culture is the national costume, the deel, a long gown made of brightly coloured, usually patterned silk that buttons up to the neck on the right side. The deel is worn by both men and women, but men add a sash of contrasting colour around the waist. For winter wear the deel has a woolen lining. The main holiday, celebrating the Lunar New Year (Tsagaan Sar), in late January or early February, is a three-day event that begins with a family feast on the eve of New Year’s Day. The New Year holiday is a time for wearing one’s best clothes, visiting relatives, exchanging gifts, and following ancient rituals of respect for one’s elders. Buddhists visit the local temple or cairn (ovoo) to give thanks. For the next two weeks at least, the particularly devout observe new-year astrological forecasts, which, for example, encourage business and trade on the fourth day of the new year or restrict travel to even-numbered dates.

Mongols have always been concerned with protecting their ancestral heritage and still practice exogamy, believing it wrong to marry within the clan. Families once kept family tree charts, with names recorded within a series of concentric generational rings. However, family trees, aristocratic titles and clan names (oyag) were banned in 1925, labeled by the socialist regime as aspects of “feudalism.” In the Law on Culture, adopted in April 1996, the legislature decided to revert to the earlier practice of keeping family trees and using clan names, and regulations for this were issued in January 1997. Clan names are now recorded on identity cards and other official documents but otherwise are little used. Thus, Mongolian citizens have three names: a clan name; a patronymic (etsgiin ner), which is based on the father’s given name; and a given name (ner).

The arts

Mongolian literature evolved from a wealth of traditional oral genres: heroic epics, legends, tales, yörööl (the poetry of good wishes), and magtaal (the poetry of praise), as well as a host of proverbial sayings. These genres are infused with what Mongols regard as a national characteristic—a good-humoured love of life, with particular fondness for witty sayings and jokes. From the 17th to the 19th century, Dalan Khuldalchi (literally, “Innumerable Liar” or “Multifibber”) was the source of humorous folktales, such as, “How to Make Felt from Fly’s Wool.” There are stories about the badarchin, wily mendicant monks, while khuurchins—bards—carried down the oral epics and ballads. The religious mysteries, tsam and maidari, banned in the 1930s under the antireligious policies of the socialist regime, are being revived in the monasteries, the participating lamas dressed and masked as the gods of Tibetan Buddhism. Episodes of these are staged by actors for tourists.

The most important Mongol literary work, the Nuuts Tovchoo (known in English as The Secret History of the Mongols)—a partly historical, partly legendary, and almost contemporary account of the life and times of Genghis Khan—was virtually unknown until a copy of it was found by a Russian Orthodox monk in Beijing in the late 19th century. It was written in Chinese characters, transcribing the medieval Mongol language, which made identification difficult and led to misunderstandings about its authenticity. The Secret History has since been published in many versions, including the old Mongol script and modern Mongol in Mongol Cyrillic, and it has been translated into English and other foreign languages. Specialists are still studying it as a historical source, as well as a key to the development of the Mongol language.

In literature, the poems and short stories written by Dashdorjiin Natsagdorj in the 1930s were taken up by the communist authorities as examples of Mongolian “socialist realism.” His best-known poem, “My Home” (“Minii Nutag”), praises the natural beauty of Mongolia. He also wrote an opera about the revolution known as Uchirtai gurvan tolgoi (“Three Sad Hills”), which is still performed today. Natsagdorj died an early death in 1937 shortly after being released from a short period of imprisonment (on false charges). There is a memorial dedicated to him near the Choijin Lama temple. On the other hand, scholar and writer Byambiin Rinchin, a contemporary of Natsagdorj, was attacked for his novels because they were considered “feudal and nationalistic.” Rinchin was also imprisoned, but he survived the purges of the late 1930s and died in 1977. He became one of the most influential writers of the historical novel genre, which emerged in the 1950s.

Among other notable Mongolian literary figures are writer and journalist Tsendiin Damdinsüren and poet Ochirbatyn Dashbalbar. Damdinsüren (1908–88), a translator of Russian novels and also at one time accused of “bourgeois nationalism,” wrote the words of the Mongolian national anthem and produced a three-volume commentary on Mongolian literature. Dashbalbar (1957–99), who attended and graduated from a literary institute in Moscow, made his name as a member of the Mongolian parliament (served 1996–99). A line from one of his poems, “In your lives love one another, my people!” was his epitaph.

The State Academic Drama Theatre (founded 1931) and the State Academic Theatre of Opera and Ballet (1963), both in Ulaanbaatar, (Ulan Bator) perform both Mongolian and Western classical works. There also is a puppet theatre in the capital. The country’s circus troupes were once popular both within Mongolia and internationally, but the fate of the remaining ensemble is uncertain, and its circus arena is in disrepair. Folksinging, music, and dance companies perform in national dress with traditional Mongolian musical instruments, such as the morin khuur (horse-head fiddle) and yatga (a kind of zither). The Mongolkino film studio has made an increasing impact at international festivals with its wide-screen epics, notably about Genghis Khan. On the other hand, films about closely observed country life have included internationally acclaimed gems such as Story of the Weeping Camel (2003).